Think Big – Beijing’s Quest for World Power

Rafael Strub – 01.06.23

The Chinese advanced civilization dates back 4000 to 5000 years and is the only one to still be alive. Especially its historical development is highly remarkable. While Europe developed slowly, an advanced civilization had long since established itself on Chinese soil. Numerous symbols can be used to describe China’s unique development. One of them is the Great Wall of China: It is one of the “Seven New Wonders of the World”, and its construction is said to have taken about 2000 years. It is said to have been built in large parts during the Ming Dynasty (1386-1644) as a protective structure to secure the border. Since then, it has been regarded as a symbol of Chinese culture.

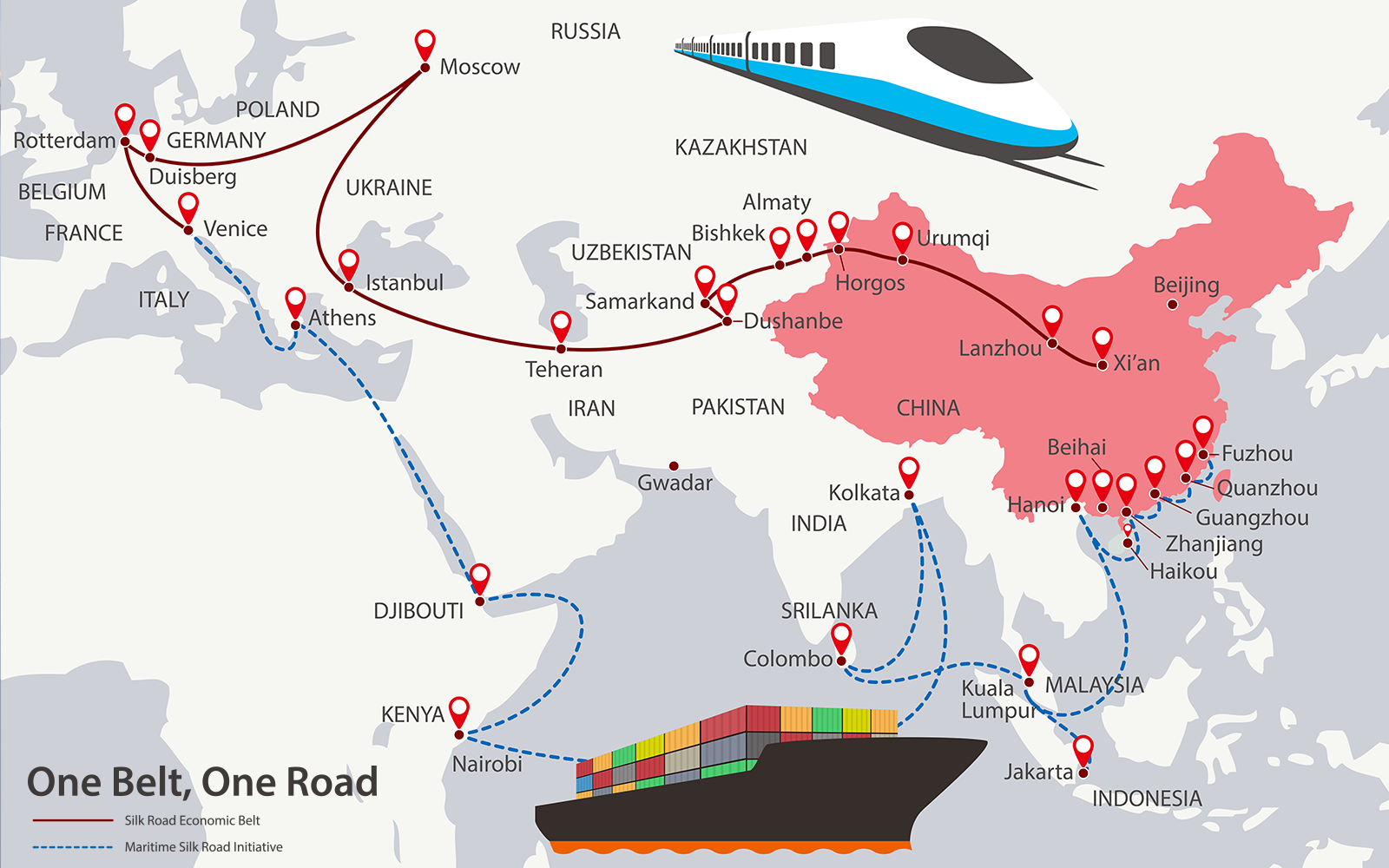

This propensity for immense construction projects is now also evident in China’s gigantic “New Silk Road” project (also known as the “Belt and Road Initiative”). The plan for the creation of the new trade routes (see graphic) is based on China’s ambitions, which have been ambitiously defined since the beginning of the 2nd century. Since Xi Jinping took power as autocratic president of the People’s Republic of China in 2013, his government has emerged more clearly than ever from the shadows of America and Europe and is openly communicating its great power aspirations. While Europe in particular is pursuing a value-driven policy, China is pursuing a strongly pronounced interest-driven foreign policy (realpolitik) – or in Trump’s words: “China First”. Besides all the existing problems (real estate bubble, an aging and recently for the first time declining population) and moral as well as human rights reservations, we should show respect for the economic success story of the – until recently – most populous economy in the world (India has recently replaced China as the most populous country on earth). The rise of Shenzhen, now a city of millions as well as a showcase city, is an impressive illustration of this growth story.

A United Nations report calls Shenzhen the fastest growing city in human history from 1980 to 2010, and (along with India’s Mumbai) the youngest city in the world with an average age of 29 years – compared to London’s average of 35 years, New York’s 36 years and Berlin’s 43 years. 40 years ago, Shenzhen had only about 60,000 inhabitants. Today, the population is around 18 million. Furthermore, the city is considered the “Silicon Valley” of China – 5G was developed in the metropolis and public transport is almost completely electrified. The rapidly growing domestic market is thirsty for imports as well as exports and requires new trade routes. The Belt and Road Initiative is intended to remedy this situation.

The now completed transformation from the world’s workbench to a high-tech giant underscores China’s global economic position in a remarkable way. The Chinese government is to invest more than one trillion U.S. dollars in ports, bridges, railroad lines and roads in more than 100 countries – the Belt and Road Initiative is thus a worldwide infrastructure project on a colossal scale with the sole aim of cementing China’s global supremacy – following the historical model of the former “ancient Silk Road. More than 70 countries are already part of the “New Silk Road,” which is intended to link the continents of Africa, Asia and Europe even more closely in terms of trade through a gigantic network of roads, ports and rails. The USA, however, is left out of this process.

In China, the widely cited trend toward deglobalization does not appear to be taking hold for the time being. On the contrary, the country was Germany’s most important trading partner for the seventh year in a row in 2022. The downside: Never before has Germany’s trade deficit been so high; in 2019, it was only one-sixth of the 2022 deficit. This allows for manifold conclusions. But one thing is clear; China is aware of its strengths and is playing to them. For example, the Chinese government is increasing the pressure on foreign companies to produce locally. This in turn accelerates the transfer of human capital and technology. In addition, the proclaimed “Dual-Circulation” and “Made in China 2025” strategies are the industrial policy master plan to make China more self-sufficient. Even though this is intended to increase Chinese domestic demand in particular, China also wants to become a highly developed country with global technological leadership. This project requires new and more efficient trade routes.

According to China’s head of state Xi Jinping, Chinese freight trains now reach over 200 cities in 24 European countries. In addition to these rail routes, ports in Africa and Europe are a key factor in China’s expansion strategy. The port of Piraeus has been owned by majority shareholder Cosco (China Ocean Shipping Company) since 2016. The Chinese state-owned shipping company is one of the largest container ship shipping companies in the world and is considered the world’s largest port terminal operator. For China, the port of Piraeus represents an elementary hub for effective land and sea connections between Asia and Europe, as well as subsequent fine distribution to Europe’s cities.

But the expansion strategy also has weighty disadvantages for China’s partner states – they place themselves in a massive dependency. It is not uncommon for serious accusations to be made. The tenor of the accusations is that the loans granted by China to third countries are one-sided, that China is practicing modern colonialism, and that it is using its own state-owned enterprises with its own personnel for infrastructure projects (for example in Serbia or Montenegro). It is more than questionable whether the flow of capital in favor of the favored third countries, which has taken place through loose lending, can ever be repaid. As a consequence of defaults, increased Chinese influence is likely to be exerted on the states mentioned.

One thing is clear: China is pursuing its plans with an iron fist and knows how to use its strengths. But in many places – especially in Europe – China’s path to “silent invasion” is being smoothed by the European Union looking the other way and not pursuing a unified strategy. It will take some skill and agility to counter the further expansion of China’s political influence through economic dependencies. In Germany at least, opposition to a possible entry by Cosco into a Hamburg container terminal now seems to be solidifying. Apparently, the German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) is said to have recently classified the Tollerort terminal in question as critical infrastructure, which means it is considered to be in need of special protection. Last October, the German cabinet agreed that Cosco could acquire only 24.9 percent of the terminal instead of 35 percent as originally planned. But this deal could now be dropped due to the new classification by the BSI.

The descriptions impressively show how China consistently pursues an ambitious growth strategy and instead of thinking in terms of years, thinks in terms of several decades (see China 2049 initiative – 100th founding anniversary of the People’s Republic of China). China divides minds, moving us between fascination and apprehension about an unknown giant – but one thing is certain: Asia’s potential is far from exhausted and offers a variety of investment opportunities in addition to the well-known risks. As long-term investors, investments in Asia – especially with a focus on China – have enjoyed a fixed place in our broadly diversified portfolios for some time.